Letters to the Editors: "Within Landscapes"

Plus some info on the LPRU's plans for the forthcoming year...

Hello from us at the LPRU! We hope this finds you well. After a quiet summer, we’re once again beginning to publish some of our ongoing research into the Lye artefacts, and aiming to share at least one more long-form written piece before the end of this year.

The full recording of Kiran Leonard’s arrangement of ‘Song of the Husband’, initially intended for the autumn, has unfortunately been set back to early 2021; we’re told this is due to ‘unforeseen technical difficulties’, and a significant expansion of the original release plan. We will keep you posted on its progress.

In the meantime, we wanted to share with you a letter we received from a reader on the subject of two of our articles, both of which feature changing depictions of landscape. We’re always interested in hearing your thoughts on our work; if you would like to contact us, please direct your inquiries to lyeplanetresearchunit@gmail.com .

To whom it may concern,

First of all: many thanks for the research you are currently undertaking and for the excerpts on display at lpru.co.uk. Very exciting work!

I'm writing in the last spate of English summer sun from a flat in South London (not far from the roundabout at Elephant and Castle) where my partner and I have called home for many years. That is, at least, it’s our home for the time being, as our whole building is set to be demolished – ‘regenerated’, excuse me – before the year is out, now that esteemed professionals have let us know that unbeknownst to us, all this time, we have been living in some blighted eyesore hardly worth the upkeep. Southwark Council’s been as hopelessly inadequate as you’d expect, the rehousing programme typically piecemeal and the compensation on offer a total pittance, and so it’s likely we’ll soon be forced out of the borough and perhaps the capital altogether. We'd seen what had happened to other neighbouring estates over the years, and so expecting this sort of technocratic, abusive strong-arming – what I can only describe as a casual disregard for all human life – we have unabatedly fought this development from the beginning. Unfortunately, for all our efforts, defeat now seems a foregone conclusion. Perhaps it always was. As you can imagine, existing in this limbo for months on end has taken a significant toll on my partner and I, and so the various revelations in the Unit's inaugural essays have proven a welcome distraction throughout the summer.

Two articles in particular have been weighing on my mind, and I have a few questions and interpretations of my own I wanted to share. I've been thinking a lot about our emotional entanglement with landscapes; the marks they leave on us and we on them. While studying the artefacts in these articles, I was struck by my immediate recognition of alien terrain, rendered by the hand of a non-human species. The terrain is not entirely physical, though the physical is one of its constituent elements; I did not recognise it because I had walked there but because I had felt there, felt that landscape and the relationships between its ambiguous figures.

Let me explain. I'm aware that Dr. Whorrall-Campbell's short piece on the Diagrams is the first in a series, and don't wish to spoil or preclude any further revelations in coming instalments with my speculation. All the same, I am anxious to learn more about what I believe to be the most intriguing aspect of these drawings: the communion of physical and abstract images, and of those which fall somewhere in between. Correct me if I’m mistaken, but I can find no other example in the published artefacts of an image without a clear physical reference. [1] I have been asking myself what the significance of this could be: this joining of clear, quite mundane objects (apparent even to the human eye) with self-evidently artificial ‘props’.

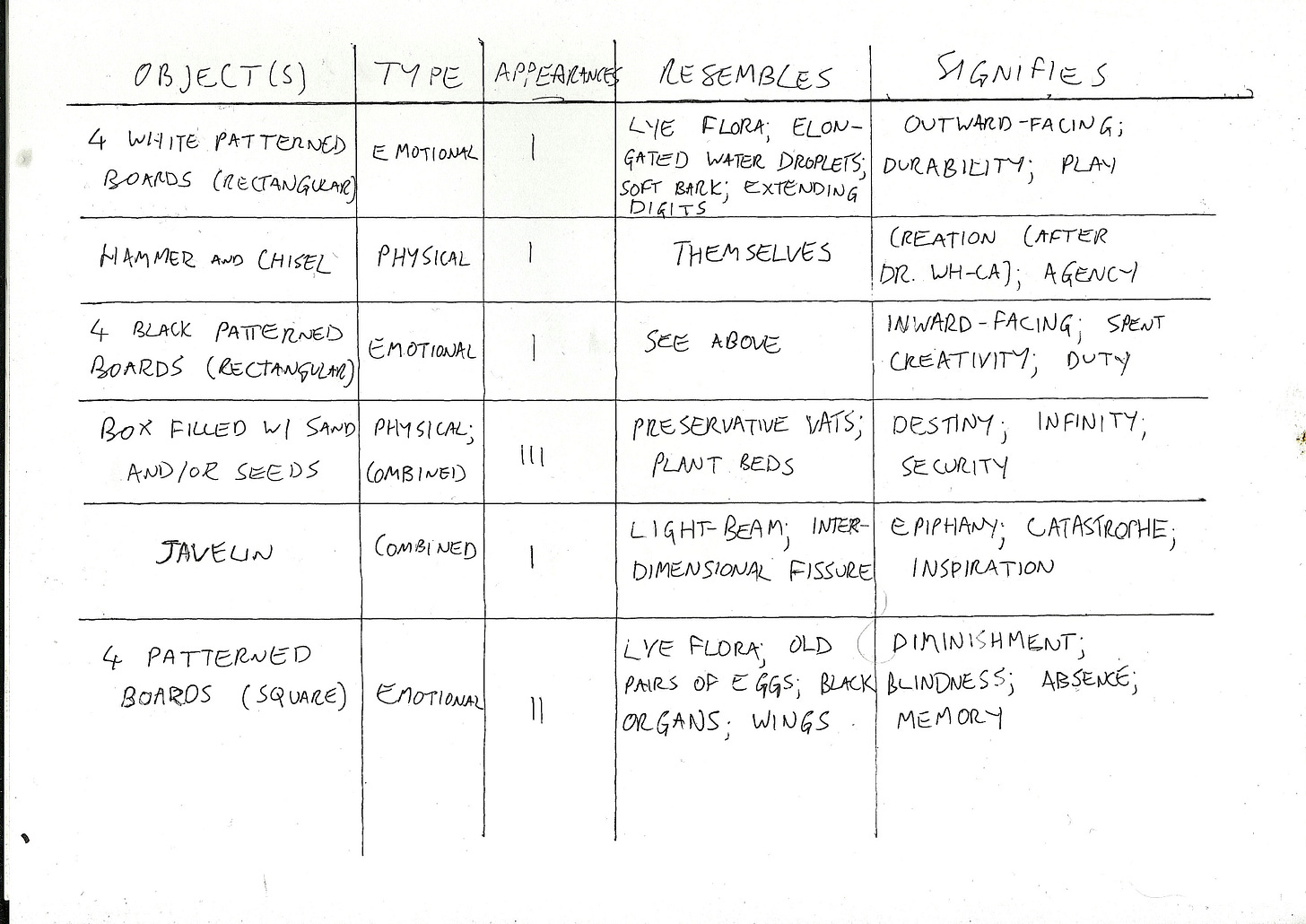

I've done my best to list and categorise the objects (or ‘forms’) depicted in the five drawings in this table. A reading of the table alongside the images in Dr. Whorrall-Campbell’s article should help to clarify how I interpret their narrative:

Now, we know that there is no shortage of Earth paintings in which landscape is used to convey a certain emotion, yet here the equation is very different. Landscape is not simply used to convey emotion. The author (authors?) of these drawings do not have a Romantic, paternalistic grasp on the world; they are not individuals conquering mountains or reappropriating tales from myth, who imbue the landscape with metaphor, who treat their surroundings like a private mirror. Nor do they weep for Mother Nature, that well-worn, venerating, yet ever so patronising catch-all for all things non-civilised. I think of pathetic fallacy – that old trick, yes, the one we all remember from secondary school English – in which a line between ‘human’ and ‘non-human’ is implicitly drawn, where the glory and might of the world is unsubstantiated without personal triumph or woe. Such techniques fail to acknowledge that our emotions, our creative faculties, and our landscapes intertwine on a level playing field. In the drawings it’s as if they are in a dance, leaderless. The author(s)’ feelings don’t ‘inhabit’ the landscape, or take ownership of it, but instead ‘become’ their own abstract forms alongside it; physical and emotional elements move amongst one another, react against each other.

I think these scenes are particularly fitting for a culture that apparently lacked our obsession with the Author and our rigid distinctions between subject and object, who spoke languages with phrases as tangibly physical as trees or stones. I believe these drawings prove that the same applied to non-verbal impulses; there is no ego here, no single guiding hand, but feelings disembodied from a shared point of origin – the body common to all Lye inhabitants and to all constituents of the world-organism. This is not a ‘personalised’ landscape, exactly, but a physical/emotional terrain they collectively had to traverse. [2]

(For the record, I would be intrigued to know how Dr. Whorrall-Campbell decided on their arrangement of the images. Were there further clues discovered in the vats which suggest this sequence, or is it simply the result of educated guesswork, or mere chance? I have tried viewing the images in different orders, while still bearing in mind my interpretations of the forms, and have found fascinating alternative versions of events… Viewed in such a way, I believe these images take on a cautious optimism in their self-renewal. I am reminded of the I Ching, the slow casting of the sticks, the playing out of other creative and ‘real-world’ possibilities…)

This communion of the physical and the emotional is thrown into sharp relief when considered in light of the Decline. As I believe I’ve shown, the division between outer and inner life has been irreparably shattered by this catastrophe. Individuals have to navigate them both as one terrain; this landscape is marked with the ever-changing physical and emotional refuse of the Decline, as well as, unavoidably, the remains of the dead, something which I think is hinted at in the drawings but made unflinchingly clear in the Monan Graves. As a summation of our entanglement with landscape, depictions of burial are as direct, as literal and sober, as possible. Nevertheless, in their varied and specific positioning of bodies one can still find the same emotion and ritualism of the diagrams.

Again, the depicted ‘objects’ are mostly arranged in circles, although in the graves they are discombobulated, broken and multi-layered; possible configurations are not just spread across illustrations but chaotically attempted on top of each other. There is no clear narrative progression (according to Monan, we cannot even be sure whether these were plans for future graves or depictions after the fact, random patterns forced into shapes of ordered significance). In their careful geometry, the presence of an ‘author’ trying to reconfigure the land is made explicit, yet the predominance of the physical – that is, of the dead – lends the graves a fatalistic, rather desperate quality not found in the open-ended, speculative world of the drawings. Here, all possible configurations are written into the ground; with all avenues exhausted, depleted of all future realities, the dead now have to lie down in the past. Darkest of all is Monan’s suggestion that the very act of dying in this pre-ordained arrangement was some last-ditch attempt to inscribe meaning onto the world…

It’s not something I like to dwell on, anyway. It’s obviously all a miserable business, in the end, and not at all what I think should be taken away from the artefacts or your work. For me, it was the whole ‘landscape relationship’ that was of interest – the fact that these drawings don’t just try to ‘depict’ the landscape from afar, but showcase what is a mutually complicit engagement. There’s no single perspective. I just wanted to put it all into words, although I still feel like I’m grasping to describe the dynamic that I sensed in these artefacts… one wholly divorced from the old paradigms of dominance. It was something quite new to me: something like a world or voice without subject.

I could go on but I’ll spare you, now that it’s dark and I have to get dinner on. Many thanks again for your research, for these little fragments of the past each pointing in a myriad of possible directions. I will make sure to keep you posted regarding our living arrangements, and the uncertain future of my own surroundings.

Yours,

-Chris Kershaw,

Calmington Road Estate Action Group (2015-)

[1] Editor’s note: At time of writing, with the exception of the Diagrams, the LPRU has released images of children's garments; sketches of flora; sculptures of huddling individuals; and plans of unknown purpose, possibly for mass burial. Of these, only the decorative circular patterns on the garments could be considered 'abstract' (that is, lacking clear physical reference; but even here the circles could be intended to represent moons, or perhaps the Planet itself).

[2] Author’s note: I confess that one inconsistency in this reading is the presence of the hammer and chisel; why is it necessary to draw attention to the artifice of these ‘emotional’ objects when there is nothing artificial about them? Is this a subliminal and provocative championing of active, creative mediation with the world?